This content is available thanks to subscriber support. To subscribe to the full newsletter, see subscription options here or click the button above.

Add the MLSS30 promotional code at checkout and get 30% OFF!

I was very excited about uranium a year ago. The entry of Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) into the market had put the spot price into a steady climb. Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine added all kinds of supply risks the market.

I had positioned for that excitement in the fall by adding a slew of uranium stocks to the portfolio. Those stocks did not do well in 2022. With inflation, rate hikes, and recession dominating the headlines, the overall stock market slid and took uranium with it. After all, uranium is a growth story – energy always is – and growth was not at the fore.

Call me stubborn or convinced, but I am still excited about uranium. While the rising spot price did several mine restarts, it’s not enough to fill the gap. There’s a gap today, which matters if you believe that the spot market is close to cleaned out (I think it’s getting very tight). And while supplies might meet in 2027 and 2028, beyond that the gap gets very large.

That gap sits in direct contrast to a nuclear renaissance. I don’t think I’m overstating that: in 2022 country after country announced plans for new nuclear plants or cancelled plans to shutter plants. Nuclear is fundamental to the world’s energy future.

I think that clear reality will put our lack of uranium in the spotlight in the coming year(s), just as soon as we get through whatever this recession turns out to be. Forward-looking investors will want real assets to ride the recovery; real energy assets will be sought in particular.

Amidst all of that, the uranium market is splitting in two. Russia has long produced significant uranium (a good chunk through Kazakhstan); the country is also home to over a third of the world’s conversion facilities and almost half of its enrichment capacity. Conversion and enrichment are essential steps in turning U3O8 into nuclear fuel. While official sanctions against Russian uranium or processing are not in place (yet), western utilities are self-sanctioning, seeking non-Russian pounds and processing capacity. There isn’t enough processing capacity in particular and that (1) is adding to the supply gap because strained facilities use more uranium and (2) will soon bifurcate the market, such that US-friendly uranium carries a premium price.

I go through all these considerations in my article. After that, I assess the uranium stocks that are currently in the Maven portfolio in the context of current market dynamics, holding most but selling a few. I also add a holding and suggest several ASX uranium stocks for those who are comfortable buying in the Australian market. There’s no great barrier there but I limit the Maven portfolio to North American markets to avoid that small barrier and simply because there are already more stocks in North America than I can assess!

Looking Back

2022 was a frustrating year for uranium investors like me because the sector failed to respond to a very bullish supply-demand backdrop. Making things even worse: the spot price actually ended the year up 14% (after spiking on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, settling back, then running again before easing) but uranium equities declined 21% on average.

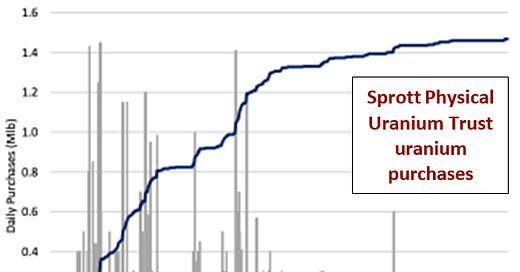

Lack of investor interest hurt equities, for sure, but also failed to help the spot price. What I mean by that is: the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) can only buy uranium to lock away in its stockpile when its stock trades at a premium to the net value of its assets (NAV). With investors not leaning in, SPUT didn’t meet that bar very often last year, which means the trust was not able to add notably to uranium demand like it had in late 2021 and in the first few months of 2022. The chart below shows SPUT’s daily (in bars) and cumulative (the line) uranium purchases; you can see how much buying eased in the last eight months.

If you talk to the team at SPUT today, they believe the spot market is “almost cleared out” of uranium. If true, that would mean that any buying by SPUT in 2023 could juice prices quickly.

Kazatomprom (KAP) buying in the spot market could do the same. Yellow Cake (another uranium holding fund) has an option to buy $100 million worth of uranium from KAP; if Yellow Cake exercises that option, KAP may have to buy in the spot market because supply chain challenges have its mines under some pressure.

And another large physical uranium fund is getting set to launch. ANU Energy, based out of Kazakhstan, has already raised US$74 million and is looking to raise another US$100 million shortly plus US$400 million on its IPO. If that all happens, ANU buying is another force that could suddenly juice the spot market.

Supply – Demand

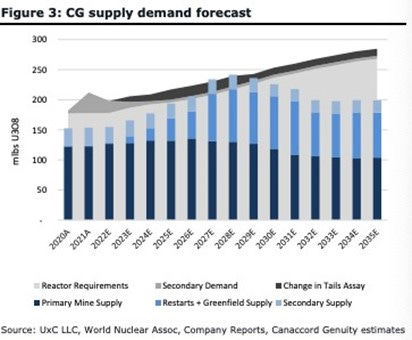

Let’s be very clear: primary mine supply remains well below global demand. Mines produced about 130 million lbs. in 2022; the world consumed 180 million lbs. It’s that gap that’s driving prices higher, to be sure, if in fits and starts. Prices strengthened enough to spark several mine restart announcements in 2022.

These announcements help fill the gap but they are not enough. It doesn’t help that the secondary supplies that long bridged the difference between mine supply and utilities needs keep shrinking (enricher sales are now gone, supply from decommissioned warheads is now very limited, stockpilers aren’t selling, etc.).

And while US$50 per lb. is enough to make restarts make sense, it is not a strong enough price to incentivize the development of new mines.

And we need new mines because nuclear power is on the rise.

Global nuclear capacity currently stands at 394 GWe from 437 operable reactors. Against that context, consider that there are 60 new reactors under construction in 18 countries.

Through 2022, rising concerns around the world (though especially in Europe) about energy security sparked a record number of nuclear power plant restarts, extensions, and new build announcements, all of which added new demand to forecasts. Uranium demand is now expected to grow 3% per annum through to 2035 (up from 2.8% per annum previously).

Japan is accelerating the restart of seven of its idled reactors

South Korea is reversing a policy to phase out nuclear and will instead boost investment in the industry

Nuclear was included in the EU’s sustainable taxonomy, creating new low-cost green funding opportunities

India announced it will build more nuclear power plants; in December the government approved 5 new sites and 10 new 900 Mwe reactors

The US Inflation Reduction Act included a tax credit to support existing reactors and provides US$70 million to incentivize the development of domestic sources of nuclear fuel

Belgium approved 10-year extensions for two of its reactors

France announced it will build at least 6 new reactors and is considering another 8; they will not close any existing reactors.

Germany decided to keep 2 of its 3 plants online at least through winter…

That brings us to the bottom line of the uranium story: supply might meet demand in 2027 and 2028 if greenfield mines come online as hoped/expected, but aside from those years there is not enough supply (the bars below) to meet demand (the shading behind). And those greenfield mines are by no means guaranteed, subject as new mines are to permitting and capital markets.

A Market Splitting in Two

No uranium discussion today would be complete without addressing how the market is splitting into two. There are, fittingly, two parts to this bifurcation: uranium processing and US government moves.

Russia has long played a key role in the nuclear fuel cycle, offering 38% of the world’s conversion capacity and 46% of its enrichment capacity. (Conversion is changing U3O8 to UF6, a gas; enrichment is centrifuging that UF6 gas to separate the more fissile U-238 from the more common but more stable U-235, a necessary step in making nuclear fuel.)

Now Western utilities are moving to cut reliance on Russia. The shift is very apparent in today’s record-high SWU (the unit used to price enrichment) and conversion prices (up 123% and 150% in 2022).

What matters here for investors is that Western enrichment capacity cannot meet projected demand. Enrichers will try, though, and the way they try is called overfeeding.

I’ll restate my lemonade analogy to explain. When lemonade demand is low, lemonade makers aren’t pressured and so will take the time to squeeze every possible drop out of each lemon. That’s underfeeding – using fewer lemons to make the same amount of lemonade – and it leaves lemonade makers with extra lemons that they sell back into the market.

When lemonade demand gets hot, lemonade makers focus on making as much lemonade as possible. To that, they process more lemons less efficiently. That’s overfeeding – using more lemons to make the same amount of lemonade, just faster – and it does the opposite, adding new lemon demand rather than adding to supply.

For enrichers to pivot from selling their surpluses to needing to buy extra is adding uranium demand in what’s already a very tight market.

So increased uranium demand is one side of the market bifurcation story. The other side is how the US government is trying to encourage domestic uranium production and is establishing a uranium stockpile.

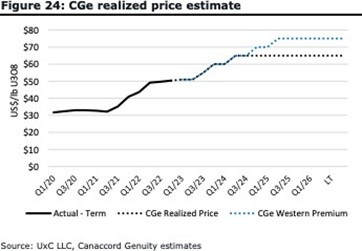

The US is establishing a Strategic Uranium Reserve filled with pounds from US mines. The problem is: there are very few operating US uranium mines. For years, the US has been heavily dependent on Russia for uranium. The lack of US production is apparent in the prices the government paid in the last few months to lock in its first 1.1 million lbs. (contracts ranged from US$59.50 to US$70.50 per lb., well above spot).

This side of the bifurcation story matters to investors because it is very likely that western uranium will command a higher price than Russia-related uranium within a year, perhaps two. Western utilities are already choosing to move away from the uranium and nuclear fuel that Russia touches. A line will be drawn in the sand if the US passes legislation requiring US utilities to only use friendly uranium (the net would likely include the US, Canada, and Australia at the least). Such a move would clearly divide the market. Canaccord’s analysts are expecting just that – two different markets – by 2024, with western uranium trading at a premium.

The Uranium Portfolio – Past and Present

I was very keen on uranium at this time last year. The fundamentals were strong and Russia’s invasion seemed like the straw that would break the utilities’ backs and send them running to sign contracts, kicking off a strong bull market. To position for this, I bought a host of leading uranium stocks with a plan to simply hold them and ride the wave.

Of course, it didn’t pan out like that.

The lesson is that, while a bull rationale for a commodity is a key starting point, details matter. Here, the details that mattered were overall investor malaise (it’s hard to kickstart a bull market when recession and inflation-fearing investors just aren’t buying) alongside growing pressure to make US uranium again.

The former erased an opportunity but the latter kept certain stocks above the fray…and gives them advantages going forward.

Investor malaise is still an issue. Many investors, focused on the pending recession, are not buying energy stocks of any sort. Yet.

That will change as the recession happens. In fact, investors love riding real assets out of a recession so this negative setup could ironically help uranium once we get to the other side.

And on the other side, US uranium producers could very well outperform everything else. Those producing uranium into the void, overall and especially of US-sourced uranium, will be prized. And there are not many stocks in the US production category.

Since US uranium is so rare, it’s widely thought the US government will also embrace uranium from Canada and Australia. That of course widens the net significantly.

Stocks in that net will outperform the rest of the uranium space. The degree of outperformance will increase dramatically if Washington legislates this ‘friendly source only’ uranium concept.

So. I want exposure to uranium. I want it primarily through advanced projects and producing mines because they (1) are large liquid stocks that will appeal to generalist investors if (when) interest rotates in and (2) carry far less risk than exploration stocks. And I prefer stocks with projects in the US or US-friendly countries.

I will still hold a few explorers because I can’t resist the potential for the huge wins that will materialize if a tiny explorer makes a strong discovery in a rising uranium market…but exploration risk is not, in my opinion, the best way to play this uranium opportunity.

This content is available thanks to subscriber support. To subscribe to the full newsletter, see subscription options here or click the button above.

Add the MLSS30 promotional code at checkout and get 30% OFF!